- Home

- UpFront

- Take One: Big story of the day

- Air India has some serious ambitions for a turnaround in five years. Will its plan work?

Air India has some serious ambitions for a turnaround in five years. Will its plan work?

By setting clear milestones focused on growing its network and fleet, and aggressively hiring talent, the airline plans to increase its market share to at least 30 percent in the domestic market while significantly growing the international routes

Manu Balachandran is a writer for Forbes India, based in Bengaluru. At Forbes India, Manu writes on automobiles, aviation, pharmaceuticals, banking, infrastructure, economy and long profiles among many others. He also moderates many of Forbes India's CEO and CXO events and hosts Capital Ideas, a podcast on the most riveting success stories from the business world. He has previously worked with Quartz, The Economic Times and Business Standard in Mumbai and New Delhi. Manu has a master's degree in journalism from Cardiff University and a degree in economics from the Loyola College. When not chasing stories, he is most likely obsessing over Formula 1 (Read: Lewis Hamilton), historical events and people, or planning long weekend drives from Bengaluru

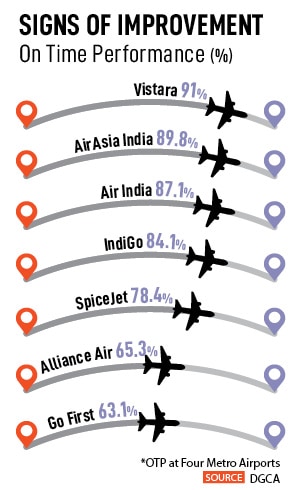

Air India’s on-time performance of 87.1 percent at the four metro airports in September this year was better than market leader IndiGo’s performance of 84.1 percent.

Image: Shutterstock

Air India’s on-time performance of 87.1 percent at the four metro airports in September this year was better than market leader IndiGo’s performance of 84.1 percent.

Image: Shutterstock

Campbell Wilson knows well what it takes to win a game of test match cricket.

Unlike T20, where slog shots and boundaries often matter more than anything else, test cricket is a measure of patience, technique, temperament, and grit. And that’s precisely why in his new role as the CEO of the Tata Group-owned Air India, Wilson is padding up to play it patiently, happy with singles and doubles to keep the scoreboard ticking, by the end of which he hopes to turn around Air India to its once-famed glory.

Related stories

“Restoring Air India to its former glory is not a T20 match,” Wilson told Forbes India in a video interview. “It’s going to be a test match and within that test match, there’s going to be patience and persistence and partnerships and maybe the occasional sixes and fours. But it’s going to be largely a function of accumulating ones and twos and building that foundation.”

Wilson took charge of Air India in the last week of July, and in the short time since, Air India, according to him, has already begun to see an improved on-time performance to start with. In April, the airline was 6th in terms of on-time performance, and by September has improved that to 3rd overall, behind Vistara and Air Asia India. By his own estimates, Air India was estimated to have been the best performer, but sister airlines Vistara and Air Asia India beat the 90-year-old carrier to it, according to the latest data from the country’s aviation regulator, the Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA).

Air India’s on-time performance of 87.1 percent at the four metro airports in September this year was better than market leader IndiGo’s performance of 84.1 percent. “So, there's been constant improvement and that then leads to some positive reinforcement. People get excited, and they see progress,” Wilson says.

Wilson joined Air India after Ilker Ayci, the former chairman of Turkish Airlines, declined to join the airline after being hand-picked by the Tata Group in February this year. Wilson came to Air India from Scoot, the low-cost arm of Singapore Airlines where he had been serving a second stint as the CEO, after initially being appointed as the company’s founding CEO in 2011.

“We do ask people to have a little bit of patience with us,” Wilson says. “We’re trying to do as much that touches the customer as quickly as possible. But we need to address the foundations, not just the superficial things.” Already, Wilson and his team have set out to do some quick fixes on the airline by replacing carpets, curtains, and seats on the aircraft while also repairing the in-flight entertainment among others that have long come under criticism for their shabby upkeep. “But it is not the final product by any means and we’re working hard on that,” Wilson says.

“Air India is one of the most challenging turnarounds in aviation history,” Satyendra Pandey, the managing partner at aviation services firm, AT-TV says. “There are legacy issues, generational issues, and cultural issues and these require a direct and unapologetic approach. The airline business continues to be a high-touch, capital-intensive and service-oriented business and Air India has to put out a product that is either exceptionally cheap or exceptionally good. All indications are it will focus on the latter and strategy will have to centre around that. A lot of these issues will not appear in data and thus data-driven decision making while important cannot be a total solution.”

So, what’s the new plan for Air India?

In September this year, Air India unveiled a new plan titled Vihaan.ai, which translates to the dawn of a new era in Sanskrit.

According to the plan, Air India says it has set itself clear milestones focused on growing its network and fleet, developing a completely revamped customer proposition, improving reliability and on-time performance, and taking a leadership position in technology, sustainability, and innovation, while aggressively hiring industry talent. Over the next five years, the airline will also look to increase its market share to at least 30 percent in the domestic market while significantly growing the international routes.

“We’ve been very clear that it’s a five-year programme,” Wilson says. “The first six months are about addressing the accumulated grievances and issues that have historically been holding the airline back, address them at war scale, and then move on to an 18-month programme of investing in systems, people, aircraft, training, internal products to make a clear statement of intent. Then the subsequent couple of years is the climb phase which is where we do all those million and one little things that are necessary to go from very good to world-class.”

“Let’s be very clear,” an industry expert said on condition of anonymity. “The Tatas did not get the best of deals. They got a broken airline, and they essentially paid for the slots because the airline is bleeding money. The path to profitability isn’t going to be anytime soon and can’t be without a couple of billion dollars. But, if there is anybody who can turn around the airline, it’s the Tata Group.”

Campbell Wilson, CEO of Air India

Campbell Wilson, CEO of Air India

Wilson is acutely aware of the serious challenges in turning around the airline. “Air India has had a challenging few decades of underinvestment and that also is reflected in the fact that there hasn’t been a lot of recruitment in key technical areas in the business,” Wilson says. “While there are some fantastic people in Air India, there hasn’t been an injection of fresh ideas or new perspectives.”

In October this year, the company announced that it received some 1,752 applications for pilots and 72,000 applications for cabin crew over a two-month period, and the company is currently assessing them. Air India had not made recruitments in non-operations areas for more than 15 years and wants to add employees into functions such as revenue management, sales, distribution, network planning, and marketing in addition to human resources, finance, and analytics among others. Last week, the airline announced the appointment of Henry Donohoe, formerly with Emirates and Norwegian Air, as its head of safety, security, and quality functions.

“The human resource factor will be the core determinant of success in years to come,” Pandey of AT-TV says. “If one looks at the most successful airlines, the single largest investment has been in people. However, cultural norms must also be factored in. Copying the West, especially when it comes to people practices, simply does not work. Whether it’s open-style offices or modes of communication–these must be seen and developed in the India context. For Air India, it is a delicate balance between continuity and change and this requires a good mix of old and new.”

In June this year, Air India offered a voluntary retirement scheme (VRS) scheme to some 3,500 people who were eligible for it, with as many as 43 percent of the employees choosing to leave the company. Air India, according to an agreement with the Indian government, couldn’t sack employees for a year. “We’re taking 250 new cabin crew each month, and we’re taking 100 new pilots each quarter,” Wilson says. “Because the airline hasn’t been recruiting for so long, the age profile skews towards older.”

In June this year, Air India offered a voluntary retirement scheme (VRS) scheme to some 3,500 people who were eligible for it, with as many as 43 percent of the employees choosing to leave the company. Air India, according to an agreement with the Indian government, couldn’t sack employees for a year. “We’re taking 250 new cabin crew each month, and we’re taking 100 new pilots each quarter,” Wilson says. “Because the airline hasn’t been recruiting for so long, the age profile skews towards older.”

Vinamra Longani, head of operations at Sarin & Co, a law firm specialising in aircraft leasing and finance, says Air India is going through what may be called a honeymoon period with the Tatas in control. “Ideally, the airline would want to capitalise on the positive buzz around the takeover to its advantage. As far as investments into the airline go, we must remember that financial institutions are usually more than willing to fund a Tata Group-backed acquisition and subsequent expansion. Their reputation precedes them.”

Off the ground

Over the past few months, the airline took 17 of its grounded aircraft to the skies and is also looking to get the 12 remaining grounded aircraft to the skies. Then, it has also been busy investing in new reservation systems, which in turn bring more traction to its website and app. “We have cleared 2.5 lakh of historic refund cases worth Rs 150 crore to try and put the past in the past and that has a positive spillover effect,” Wilson says. In addition, in October this year, the company also announced a new menu for its domestic passengers comprising gourmet meals.

“With respect to attracting fliers, the factors are all the same,” Wilson says. “Are you punctual? Are you reliable? Are you trustworthy? Does the seat work? Does the in-flight entertainment work? Those are hygiene factors and unfortunately, Air India hasn’t been consistently hitting the marker on all of those, which is why all of them are such high-priority items to address in the immediate months.”

Then, last month, Air India also signed leases and letters of intent for 30 new aircraft, including 25 Airbus narrow-body aircraft and five Boeing wide-body aircraft as part of its plan to expand its fleet size. Air India currently has a fleet size of 128 aircraft that includes 49 wide-bodied aircraft and 79 narrow-bodied aircraft. Air India Express has a fleet size of 25 aircraft. The new aircraft will join the fleet in late 2022 with the wide-bodied aircraft offering premium economy seats for the first time.

“These 30 aircraft may herald the turnaround and define what the Air India of the future would be as far as the in-flight product and service is concerned,” Longani, adds. “They may showcase what the Tata Group intends to do with Air India and the product they intend to offer. Apart from fixing the product, Air India will also then need to benchmark itself against the best in the world.”

“We’re in discussions with both of the major airframe OEMs and the associated engine manufacturers for a very significant order of aircraft which will start coming in in 2024 or thereabouts,” Wilson says. “We’ve established an objective of 30 percent domestic market share and 30 percent international market share over the next five years. There are quite a few paths to get there whether it’s through the acquisition of aircraft or other transactions. Obviously, time will tell, but we’re focused on the ambition more than the process at the moment.”

The Tata aviation play

Air India returned to the Tata Group after 68 years when the government chose the Mumbai-headquartered salt to steel conglomerate as part of its disinvestment plan.

JRD Tata, former chairman of the Tata Group, had founded Air India in 1932 and the government took over the airline in 1953 as part of a nationalisation plan. The government purchased a majority stake in the carrier from Tata Sons though its founder JRD Tata continued as chairman till 1977. The company was renamed Air India International Limited, and the domestic services were transferred to Indian Airlines as part of a restructuring.

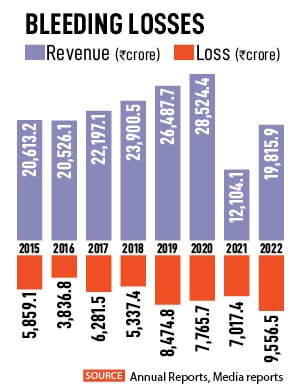

Over the years, the airline has come to symbolise everything wrong with governmental interference in the running of day-to-day operations of a company. Much of that is largely due to an ill-timed move by the Indian government in 2007 when it merged Air India—then flying internationally—with domestic carrier Indian Airlines 2007, creating a bigger entity, the National Aviation Company of India Ltd. Both Air India and Indian Airlines were making losses at that time, bleeding Rs 541 crore and Rs 240 crore, respectively, in 2007.

The merged company had more than 30,000 employees—256 per plane—in 2007, twice the global norm. That meant the company was spending almost one-fifth of its revenue on employee pay and benefits while other airlines traditionally spend only about one-tenth. Besides, the 2008 global economic collapse threw operational expenses out of gear as oil prices skyrocketed. As more private airlines took to flying on routes that once belonged to Air India, business plummeted. That meant, over time, the airline racked up debt, which stood at Rs 60,000 crore by August 2021, and was steadily losing money on operations.

The merged company had more than 30,000 employees—256 per plane—in 2007, twice the global norm. That meant the company was spending almost one-fifth of its revenue on employee pay and benefits while other airlines traditionally spend only about one-tenth. Besides, the 2008 global economic collapse threw operational expenses out of gear as oil prices skyrocketed. As more private airlines took to flying on routes that once belonged to Air India, business plummeted. That meant, over time, the airline racked up debt, which stood at Rs 60,000 crore by August 2021, and was steadily losing money on operations.

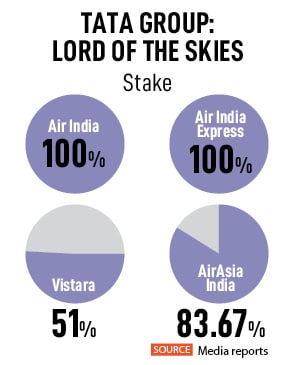

Since coming to power in 2014, the Narendra Modi government had made multiple attempts to sell the airline to private companies, before managing to complete the process in October last year. As part of its bid, the Tata group’s wholly-owned subsidiary Talace Pvt Ltd put an enterprise value (EV) bid at Rs 18,000 crore with debt to be retained at Rs 15,300 crore and a cash component of Rs 2,700 crore. Tata’s bid was higher than the Ajay Singh-led consortia’s enterprise value (EV) bid at Rs 15,100 crore. Tatas took 100 percent control of Air India, the low-cost carrier AI Express, and Air India’s 50 percent stake in ground handling firm AI-SATS.

“We must remember that there is also a considerable culture shift underway at the airline,” an industry expert said on condition of anonymity. “They are used to the sarkari mindset where decisions were taken slowly. Now those decisions will be taken swiftly and getting accustomed to it doesn’t happen overnight. There certainly will be a clash of the old guard and the new one.”

But all that doesn’t seem to be much of a concern for Wilson, who has spent a considerable amount of time at Singapore Airlines. His decision to come on board the airline, whose reputation had come under fire, was an easy affair, and there were no second thoughts about it. “This is the most exciting job in aviation today,” Wilson says.

“India is a wonderful geography. It has a fast-growing economy, a large population, and a large diaspora. When I was approached it was an interesting proposition because there’s just so much potential and now with patience, capital and ambition, there is a real opportunity to realise that potential for Air India.”

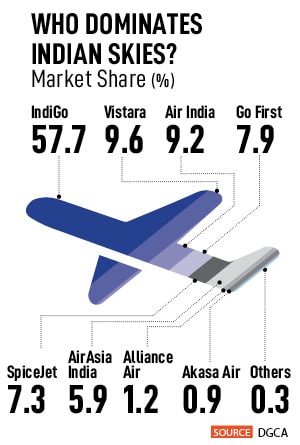

It also helped that Vistara, which Tatas currently run with Singapore Airlines, has managed to make significant inroads into the domestic aviation market with its full-service carrier offering in a market that has been dominated by low-cost carriers. Vistara was set up in 2015, and in the seven years since, the airline has emerged as the country’s second-largest airline by market share. In all, the Tata Group currently controls a 100 percent stake in Air India and Air India Express in addition to a 51 percent stake in Vistara and an 83 percent stake in Air Asia India. That makes it four airline brands under one group.

While the Tata Group had remained tight-lipped about a possible merger between the various brands, Singapore Airlines (SIA) said in October that it is exploring a potential merger of Vistara with Tata Group’s Air India. “Leaving aside the different airlines and different brands that sit under the Tata portfolio, what I see from an Air India perspective is the need for a full service and low cost proposition,” Wilson says. “So, our ambition is to build a world-class full service carrier and a world class low-cost carrier under the Air India Group and operate them synergistically.”

That means, there is a strong possibility that Air India and Vistara could emerge as one big full-service carrier while Air Asia India and Air India Express could emerge as the low-cost arm with both domestic and international operations. “I think we need to cross that bridge when we come to it,” Wilson says about possible mergers. “We have an airline to turn around and we have an aspiration to reach for Air India and we’re 100 percent focused on that task. Life does throw a googly every so often and if that comes, then we’ll play it as it comes.”

A possible merger between Air India and Vistara meanwhile could see trouble from India’s competition commission. “Both Air India and Vistara are essentially competing for the same traffic and losing money in the process,” Longani adds. “Hence, it may not make sense from a group perspective to continuously fund losses at two full-service airlines.

However, there could be concerns from the competition commission since a merger would eliminate one of two full-service carriers in India, which may impact ticket prices, especially in the premium cabins. That could however change if Jet Airways offers a business class or premium product.”

India’s domestic aviation market is currently led by low-cost carriers that control as much as 80 percent of the market, led by market leader IndiGo which corners nearly 60 percent of the market share. “There are some markets and some routes that are more disposed to a full-service proposition. Some are more disposed to a low-cost proposition. Somewhere they can accommodate both,” Wilson says. “I think domestically the evidence is quite clear that it’s largely a low-cost market, although there is a place for full service. Internationally, it’s largely a full-service market, although there is a place for a low cost [service]. How we deploy those two models is a function of how the market shape not just currently is, but also how it evolves.”

“The low-cost market in India cannot be ignored so one way or the other Air India will have to play in the space,” adds Pandey. “Usually, a dual brand strategy has worked better as it helps separate out the cost base, the proposition, and the offerings. This has been seen with airlines such as Singapore Airlines (with its low-cost arm Scoot); Qantas (with Jetstar); IAG–the parent of British Airways (with Vueling). Yet again, Air India will have to think of its strategy within its own context and see what works best.”

Path to profitability

For now, Wilson says the company has a clear path to profitability, despite consistently making losses for decades.

“We do have a path to profitability,” Wilson says. “It is clearly two-fold. On the top line, it is to attract more passengers through new revenue management systems and new destinations and improve loyalty programmes and partnerships. The second is to address the cost structure, automate, and take advantage of artificial intelligence, and modern systems. We want to bring aircraft that are currently sitting on the ground into revenue service so they can earn money, expand, so that we’re spreading our fixed costs across a larger base, and operate more reliably so we can push aircraft utilisation up a little bit more.”

That also includes improved rostering technologies to efficiently use crew, renegotiate key contracts, and bring in new aircraft that burn less fuel. “There’s no secret to success in the airline. The challenge is execution, and the challenge is doing all the very many things that need to be done together in a coordinated way. If there is a magic bullet, we would all be seeking it. But there isn’t one.”

That also includes improved rostering technologies to efficiently use crew, renegotiate key contracts, and bring in new aircraft that burn less fuel. “There’s no secret to success in the airline. The challenge is execution, and the challenge is doing all the very many things that need to be done together in a coordinated way. If there is a magic bullet, we would all be seeking it. But there isn’t one.”

Would that also mean a possible rebranding in the future? “It’s certainly an option and indeed something that we will consider,” Wilson adds. “But, first things first, let’s make the airline something that we can all be proud of, and then we can consider what it looks like.”

The 51-year-old Wilson certainly is padded up for the long innings. There could be many googlies and bouncers along the way, and he is well aware of that. But, he seems rather confident about putting on a strong scoreboard. If he manages to do so, it will certainly be one for the books.